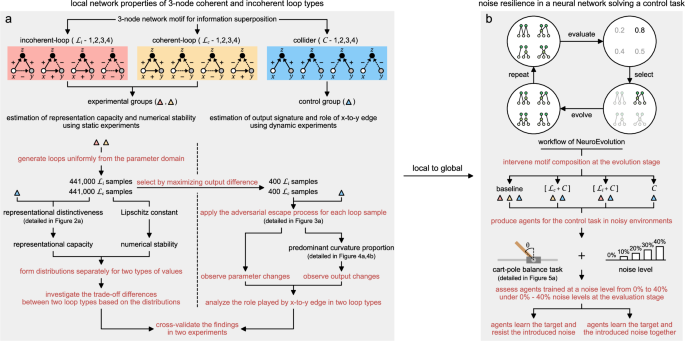

Structure and parameter domain of motifs

For the investigated three motif types, as Fig. 1a shows, each motif type comprises two input nodes (x, y) and one output node (z). For incoherent loops, they feature a mix of positive and negative influences among x, y, and z, without a consistent feedback pattern. The direction of causality between the variables is mismatched, leading to no clear reinforcing or balancing loop. In the contrary, coherent loops are characterized by a consistent pattern of influences that form either reinforcing loops, where all interactions are positive (sub-structure 1) or negative (sub-structure 4); or balancing loops, where the influences lead to system stability (sub-structures 2 and 3) even if they are mixed. For colliders, they occur where x and y independently affect z, without any direct influence between x and y.

The imposition of constraints is necessary to investigate the effects of different parameters on the representational capacity and the numerical stability of motifs. To achieve this, we impose the following constraints. Firstly, our investigation is limited to the propagation dynamics dictated by the “tanh” activation and the “sum” aggregation functions. Moreover, normalization is introduced in the weights and biases in motifs. Specifically, weights must be within the range of [−1.000, −0.001] ∪ [+0.001, +1.000], which are categorized as positive if they lie within the range of [+0.001, +1.000] and negative otherwise. Any weight within the range of (−0.001, +0.001) is removed to guarantee structural consistency with expectations. Additionally, the bias range also spans from [−1.000, +1.000]. To ensure the finiteness of calculations in the static experiment, loop samples are generated by enumeration. In this context, the positive weight set comprises {0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0}, while the negative weight set is composed of the opposite numbers of positive weights: {−0.1, −0.2, −0.3, −0.4, −0.5, −0.6, −0.7, −0.8, −0.9, −1.0}. Biases range is [−1.0, + 1.0] with an interval of 0.1.

Normalized output landscape of motifs

Binding signals to nodes in aforementioned motifs, for two input signals \(x\in {{\mathbb{S}}}_{x}\) and \(y\in {{\mathbb{S}}}_{y}\), the corresponding output signal of motif \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}\in \{{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{i},{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{c},{{{\mathcal{C}}}}\}\) is calculated as

$$z={{{\mathcal{M}}}}(x,y)$$

(1)

where \(z\in {{\mathbb{S}}}_{z}\). To fully investigate the signal propagation differences between different motif types, both input signals are normalized in the range between −1 and + 1, i.e., \({{\mathbb{S}}}_{x},{{\mathbb{S}}}_{y}\in [-1,+1]\), in this work. Based on Equation (1), all output signals in \({{\mathbb{S}}}_{z}\) can be normalized and can form the normalized output landscape L of a given motif \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}\), that is

$${{\boldsymbol{L}}}= \frac{2\times {{\mathbb{S}}}_{z}}{\max {{\mathbb{S}}}_{z}-\min {{\mathbb{S}}}_{z}}-1=\frac{2\times {{\mathcal{M}}}({{\mathbb{S}}}_{x},{{\mathbb{S}}}_{y})}{\max {{\mathcal{M}}}({{\mathbb{S}}}_{x},{{\mathbb{S}}}_{y})-\min {{\mathcal{M}}}({{\mathbb{S}}}_{x},{{\mathbb{S}}}_{y})}-1\\ = \frac{2\times {\left(\begin{array}{ccc}{{\mathcal{M}}}(-1,-1)&\cdots &{{\mathcal{M}}}(-1,+1)\\ \vdots &\ddots &\vdots \\ {{\mathcal{M}}}(+1,-1)&\ddots &{{\mathcal{M}}}(+1,+1)\end{array}\right)}_{\frac{2+h}{h}\times \frac{2+h}{h}}}{\max {\left(\begin{array}{ccc}{{\mathcal{M}}}(-1,-1)&\cdots &{{\mathcal{M}}}(-1,+1)\\ \vdots &\ddots &\vdots \\ {{\mathcal{M}}}(+1,-1)&\ddots &{{\mathcal{M}}}(+1,+1)\end{array}\right)}_{\frac{2+h}{h}\times \frac{2+h}{h}}-\min {\left(\begin{array}{ccc}{{\mathcal{M}}}(-1,-1)&\cdots &{{\mathcal{M}}}(-1,+1)\\ \vdots &\ddots &\vdots \\ {{\mathcal{M}}}(+1,-1)&\ddots &{{\mathcal{M}}}(+1,+1)\end{array}\right)}_{\frac{2+h}{h}\times \frac{2+h}{h}}}-1$$

(2)

where h is an interval for equidistant sampling if required. Theoretically, h approaches 0 and L is a continuous surface. To reduce the amount of calculation, we make h equal to 0.05 in this work; thus, L becomes a matrix of size 41 × 41.

Representational distinctiveness and capacity of motifs

To evaluate the representational capability of a loop type, we introduce the measure of representational distinctiveness, defined as the degree to which the output landscape of a loop motif resists imitation by colliders. Specifically, for a given loop sample \({{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}_{1}\) and a collider sample \({{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}_{2}\), the representational distinctiveness is quantified as the difference between their respective normalized output landscapes S1 and S2 measured by the L2 loss function:

$${{{\rm{LOSS}}}}({{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}_{1},{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}_{2})={\left(\frac{h}{2+h}\right)}^{2}\times \sum {({{{{\boldsymbol{L}}}}}_{1}-{{{{\boldsymbol{L}}}}}_{2})}^{2}.$$

(3)

Due to the parameter variations within a motif, the hyperspace of output landscapes associated with a given motif type exhibits continuity. Therefore, a larger value of the L2-norm loss indicates that the loop motif generates a more distinctive output landscape relative to the collider, reflecting stronger representational distinctiveness. Conversely, a smaller value implies higher substitutability, meaning the loop landscape can be more easily imitated by the collider. At the population level, the representational capacity of a motif type is determined by the distribution of distinctiveness values across all loop-collider sample pairs within this hyperspace. A right-shifted distribution indicates that loops as a class span a broader and less imitable region of expression space, thereby reflecting higher representational capacity.

Detection of the output signal specificity of motifs driven by the adversarial escape process

Although the replacement rate is useful in describing the motif’s representational capability, it fails to effectively communicate the underlying complexities of trade-offs that exist within the real number field of weights and biases. Our immediate objective is to investigate the cost landscape that is incurred when a motif type attempts to escape away from another motif type or when it is challenging to represent using another motif type. Inspired by the generative adversarial network36, we employ a gradient-based strategy, termed maximum-minimum loss search, to drive this adversarial escape process.

The illustration of this process is shown in Fig. 3a. Two motifs from different motif types are initialized either randomly or specifically. The maximum-minimum loss search contains two iterations: the maximum iteration (as the external circulation, or round in this work) and the minimum iteration (as the internal circulation). Here, we take two motifs ℓ and c, one in \({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{i}\) and another in \({{{\mathcal{C}}}}\), as an example. The parameters of ℓ are fixed in each minimum iteration, and the most similar collider c* can be obtained by the gradient descent from ℓ, that is,

$${c}^{*}=\arg {\min }_{c}{{{\rm{LOSS}}}}\left\{\ell,c\right\},$$

Contrariwise, for the maximum iteration, the parameters of ℓ can be adjusted by the gradient ascent, using the loss value between ℓ and its most similar collider c*, thus,

$${\ell }^{*},{c}^{*}=\arg {\max }_{\ell }{{{\rm{LOSS}}}}\left\{\ell,\arg {\min }_{c}{{{\rm{LOSS}}}}\left\{\ell,c\right\}\right\}.$$

(4)

The process of searching the maximum-minimum loss LOSS(ℓ*, c*) can be regarded as the process of ℓ or \({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{i}\) escaping from \({{{\mathcal{C}}}}\).

Numerical stability of motifs

Given two metric spaces (X, dX) and (Y, dY), where dX and dY denote the metrics on the sets X and Y, respectively. A function f : X → Y is said to be Lipschitz continuous if there exists a real constant K ≥ 0 that satisfies the inequality

$${d}_{{{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}}}\left(f({x}_{1}),f({x}_{2})\right)\le K\times {d}_{{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}({x}_{1},{x}_{2}),$$

for all x1 and x2 in X. In this study, we define the minimal K as \({\mathbb{C}}\), which is understood to represent the Lipschitz constant. This constant can be interpreted as the maximum rate of change of a function over a region. As such, it is generally agreed upon that a motif’s numerical stability decreases as its Lipschitz constant increases37.

To approximate this constant of a motif under normalized input signals for a normalized output landscape L,

$${\mathbb{C}}={\max }_{0\le {\delta }_{1},{\delta }_{2}\le \frac{2}{h}}\left| \frac{{{{\boldsymbol{L}}}}[i,j]-{{{\boldsymbol{L}}}}[i+{\delta }_{1},j+{\delta }_{2}]}{\sqrt{{({\delta }_{1}\times h-1)}^{2}+{({\delta }_{2}\times h-1)}^{2}}\times h}\right|$$

(5)

where \(i\in [-{\delta }_{1},\frac{2}{h}-{\delta }_{1}]\) and \(j\in [-{\delta }_{1},\frac{2}{h}-{\delta }_{1}]\) for each given δ1 and δ2.

There is consistency in the sampling of the domain definition for the similarity calculation and the Lipschitz constant approximation. Even though the approximated constant may be less than the theoretical value, it remains useful in assessing the balance between representational capacity and numerical stability.

Curvature features of output signal landscapes

In our work, the area of ridge or valley shapes can be used for the specificity of incoherent loops compared to colliders. Since all output signal landscapes presented by “tanh” and “sum” functions are continuous, we can determine the area of ridge or valley shapes through local curvature features, specifically convex and concave surfaces. In simpler terms, if a point is located on a ridge, it is typically found on a surface that curves outward. On the other hand, if a point is part of a valley, it is usually on a surface that curves inward.

Based on Aleksandrov’s proof38, the concavity and convexity of any point in the output signal landscape can be calculated using the eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix. For a bivariate function f(x, y), its Hessian matrix H at the point (x, y) is defined as:

$$H=\left[\begin{array}{cc}\frac{{\partial }^{2}f}{\partial {x}^{2}}&\frac{{\partial }^{2}f}{\partial x\partial y}\\ \frac{{\partial }^{2}f}{\partial y\partial x}&\frac{{\partial }^{2}f}{\partial {y}^{2}}\end{array}\right].$$

(6)

The local convexity or concavity at this point is determined by the eigenvalues of its Hessian matrix. Should the eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix at this point be entirely positive, the function exhibits strict local convexity. Conversely, if the eigenvalues are all negative, it indicates strict local concavity. When the eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix are a mix of positive and negative, it signifies that the function does not have a definitive convex or concave nature at this point.

To extend from local curvature to a global measure, the surface areas corresponding to convex and concave regions across the entire output landscape were computed. The predominant curvature proportion is then defined as the ratio between the larger of the convex or concave areas and the total surface area:

$$\frac{\max \{{{{\rm{convex}}}}\,{{{\rm{area}}}},{{{\rm{concave}}}}\,{{{\rm{area}}}}\}}{{{{\rm{total}}}}\,{{{\rm{area}}}}}$$

This metric captures whether the overall landscape is dominated by convexity (ridge-like) or concavity (valley-like), thereby serving as a proxy for the extent of geometric specialization in loop outputs.

Overview of the practical task

CartPole-v0 is a reinforcement learning environment where the goal is to balance a pole on a moving cart by applying forces to the left or right side of the cart, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. Before an environment terminates, such as when the pole tilts more than 24° from vertical, a reward of +1 is accumulated. A successful agent can achieve the target accumulated reward of 195 within 200 episode steps. A more comprehensive introduction can be found in the Supplementary Section 4.

Approaches and parameter settings on neural networks composed of motifs

Neuroevolution is a type of machine learning approach that utilizes evolutionary strategies to generate ANNs28. Specifically, it operates on a population of neural networks, with their structure and parameters adjusted based on the given evolutionary strategy to produce the most appropriate agent for a given task (Supplementary Section 4). Regardless of the evolutionary strategy employed, the process of manipulating the neural network structure in this type of approach can be essentially interpreted as the selection of more appropriate motif combinations.

To investigate the influence of motif composition on representational capacity and numerical stability of overall neural networks, we make minor modifications to the well-established neuroevolution method, i.e., NEAT29. Such modifications mean screening the specific motif types during the initialization, mutation, and hybridization stages of neural networks without simultaneously optimizing weights and biases, as we did in our previous work39. This reduces the potential impact of other uncertain factors on our observation indicators. Here, four comparable methods are established: the baseline method and its three variants that involve screening incoherent loops (\({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{c}+{{{\mathcal{C}}}}\)), coherent loops (\({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{i}+{{{\mathcal{C}}}}\)), and all loops (\({{{\mathcal{C}}}}\)). Other parameter setting that matches the motif-scale experiment is organized in Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Practical definitions of representational capacity and numerical stability

The definition of representational capacity and numerical stability of neural networks in practical tasks differs slightly from that of motifs in theoretical experiments. Evolutionary strategies can generate agents with ideal training performance more efficiently in fewer generations when available motifs have higher representational capacities. If available motifs have high numerical stability, the evolutionary strategy can generate agents with ideal training performance within a similar number of generations, even in the presence of training noise. The most concerning and often overlooked aspect is that we aim for evolutionary strategies to utilize the environment and noise as separate factors in the training stage to select more suitable agents, but there is a risk that they may unconsciously conflate the two. If the numerical stability of partially available motifs is low, the “most suitable” agent produced by the evolutionary strategy may adapt to the environment only in the presence of training noise conditions. Consequently, any fluctuations in the noise level can considerably impair its performance, which can become a potential risk for training neural networks in practical tasks.

Therefore, in addition to training performance and required generations, we focus on the following two indicators concurrently. By definition, a qualified agent or an agent with “Success type (S)” implies that the most suitable agent obtained under the given noise level can achieve ideal performance (Supplementary Section 4) in noise conditions less than or equal to this given noise level. “Failure Type 1 (F1)” reflects a slightly weaker performance situation in which the most suitable agent can tolerate only noise levels below the given training noise level. Specifically, the highest noise level at which this agent can attain ideal performance during evaluation sets the upper bound for the noise level that its corresponding evolutionary strategy can learn to handle. In the case of “Failure Type 2 (F2)”, none of the most suitable agents can achieve ideal performance under any noise level, while the general trend of their performance is accompanied by an increase in noise and a decrease in evaluating performance. This circumstance may arise from slow training progress caused by the excessive training noise level, since it hinders evolutionary strategies from accurately identifying agents that have already acquired crucial environmental information. We define the easily overlooked situation we mentioned above as “Failure Type 3 (F3).” In this situation, the most suitable agent obtained under a specific noise level becomes unable to achieve ideal performance under the training noise level and performs worse while reducing the noise level.

Set the training noise to 30%, let ρi be the ideal performance (detailed in Supplementary Section 4), the mathematical definitions of the success type and three failure types are: S = {ρ0%, ρ10%, ρ20%, ρ30%} ≥ ρi, ρ40%, F1 = {ρ0%, ρ10%, ρ20%} ≥ ρi > ρ30% > ρ40%, F2 = ρi > ρ0% > ρ10% > ρ20% > ρ30% > ρ40%, and F3 = ρi > ρ30% > {ρ0%, ρ10%, ρ20%, ρ30%, ρ40%}, where ρ0% is the agent performance under noise-free evaluation process, ρ10%–ρ40% refer to the agent performance under 10%–40% level of noise during the evaluation process. For cases that do not fully match the given failure type, they are merged into the closest failure type. This work primarily focuses on the investigation of this situation.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

link